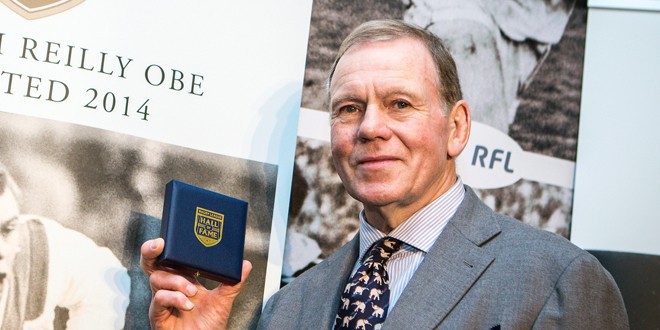

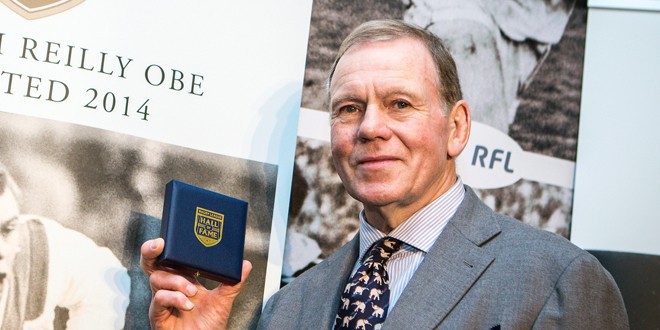

Malcolm Reilly was not just one of the great rugby players of all time, he was one of the toughest. His hard-man reputation preceded him in a career that saw him win showpiece finals with Castleford and Manly. He moved into coaching, winning the Challenge Cup with Castleford in 1986 and the Grand Final with Newcastle Knights in 1997. In between, he

Malcolm Reilly was not just one of the great rugby players of all time, he was one of the toughest. His hard-man reputation preceded him in a career that saw him win showpiece finals with Castleford and Manly. He moved into coaching, winning the Challenge Cup with Castleford in 1986 and the Grand Final with Newcastle Knights in 1997. In between, he Rugby League Heroes: Malcolm Reilly

Malcolm Reilly was not just one of the great rugby players of all time, he was one of the toughest. His hard-man reputation preceded him in a career that saw him win showpiece finals with Castleford and Manly. He moved into coaching, winning the Challenge Cup with Castleford in 1986 and the Grand Final with Newcastle Knights in 1997. In between, he

Malcolm Reilly was not just one of the great rugby players of all time, he was one of the toughest. His hard-man reputation preceded him in a career that saw him win showpiece finals with Castleford and Manly. He moved into coaching, winning the Challenge Cup with Castleford in 1986 and the Grand Final with Newcastle Knights in 1997. In between, he