It was the summer of 96. One that made Bryan Adams’ itinerary some 27 years previous look rather uneventful, as Rugby League was entering a new era. The summer era. The Super League.

A new era welcomed by near pandemonium, as a sport that was settled on the M62 corridor was undergoing a seismic shift. Animosity still lingered in the traditiona

It was the summer of 96. One that made Bryan Adams’ itinerary some 27 years previous look rather uneventful, as Rugby League was entering a new era. The summer era. The Super League.

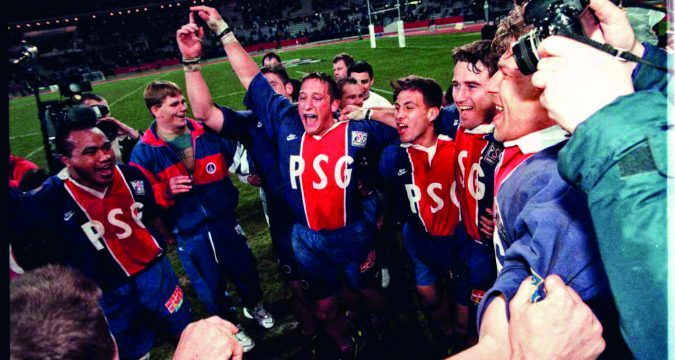

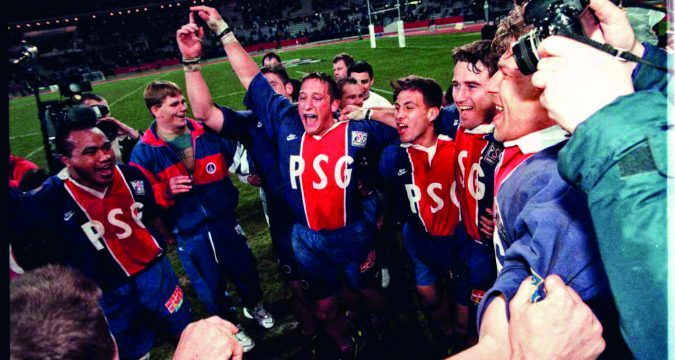

A new era welcomed by near pandemonium, as a sport that was settled on the M62 corridor was undergoing a seismic shift. Animosity still lingered in the traditiona 24 years on – The rise and fall of Paris Saint-Germain, told by the people involved

It was the summer of 96. One that made Bryan Adams’ itinerary some 27 years previous look rather uneventful, as Rugby League was entering a new era. The summer era. The Super League.

A new era welcomed by near pandemonium, as a sport that was settled on the M62 corridor was undergoing a seismic shift. Animosity still lingered in the traditiona

It was the summer of 96. One that made Bryan Adams’ itinerary some 27 years previous look rather uneventful, as Rugby League was entering a new era. The summer era. The Super League.

A new era welcomed by near pandemonium, as a sport that was settled on the M62 corridor was undergoing a seismic shift. Animosity still lingered in the traditiona