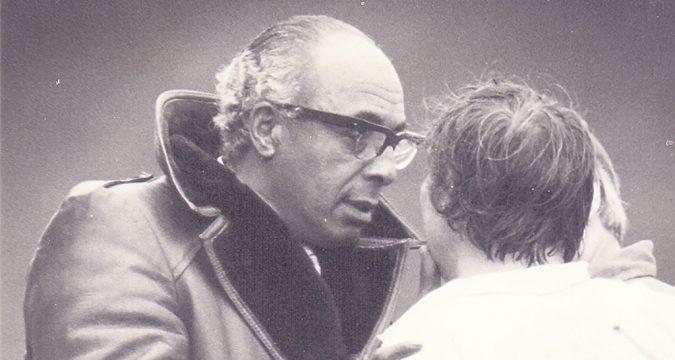

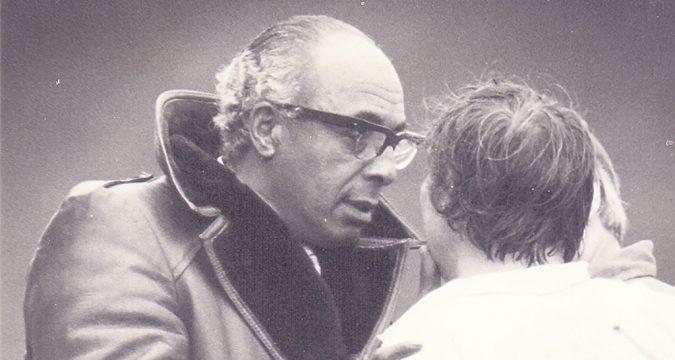

THE publication of sports historian Tony Collins’ biography of the great Roy Francis (‘Roy Francis – Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader’) reminded me once again of the historical debt rugby league has owed to Welsh converts from rugby union in the days before the union code turned professional in 1995.

And, at a time when Sir Billy Boston

THE publication of sports historian Tony Collins’ biography of the great Roy Francis (‘Roy Francis – Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader’) reminded me once again of the historical debt rugby league has owed to Welsh converts from rugby union in the days before the union code turned professional in 1995.

And, at a time when Sir Billy Boston Final Whistle: New book on life of Roy Francis a reminder of our debt to Welsh converts

THE publication of sports historian Tony Collins’ biography of the great Roy Francis (‘Roy Francis – Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader’) reminded me once again of the historical debt rugby league has owed to Welsh converts from rugby union in the days before the union code turned professional in 1995.

And, at a time when Sir Billy Boston

THE publication of sports historian Tony Collins’ biography of the great Roy Francis (‘Roy Francis – Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader’) reminded me once again of the historical debt rugby league has owed to Welsh converts from rugby union in the days before the union code turned professional in 1995.

And, at a time when Sir Billy Boston