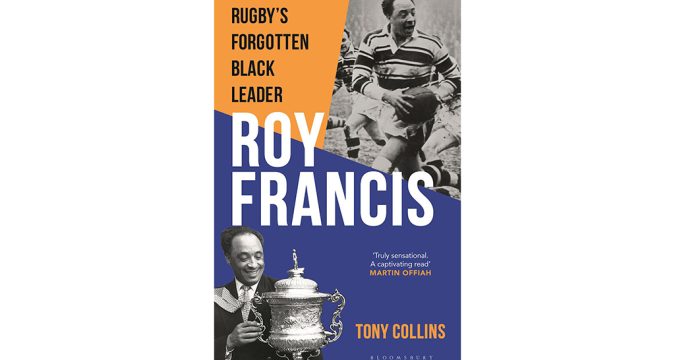

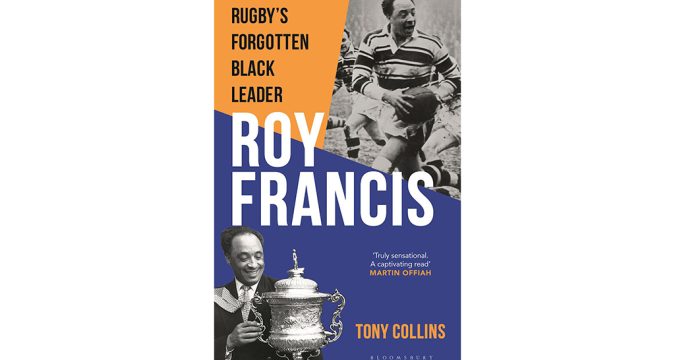

Roy Francis – Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, by Tony Collins

(Published by Bloomsbury, RRP £18.99)

League Express editor MARTYN SADLER reviews a welcome addition to the Rugby League bookshelves

TONY COLLINS has done Rugby League a great service by writing about a man who was an outstanding individual by any measure, with many great ach

Roy Francis – Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, by Tony Collins

(Published by Bloomsbury, RRP £18.99)

League Express editor MARTYN SADLER reviews a welcome addition to the Rugby League bookshelves

TONY COLLINS has done Rugby League a great service by writing about a man who was an outstanding individual by any measure, with many great ach Book Review: Roy Francis – Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader

Roy Francis – Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, by Tony Collins

(Published by Bloomsbury, RRP £18.99)

League Express editor MARTYN SADLER reviews a welcome addition to the Rugby League bookshelves

TONY COLLINS has done Rugby League a great service by writing about a man who was an outstanding individual by any measure, with many great ach

Roy Francis – Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, by Tony Collins

(Published by Bloomsbury, RRP £18.99)

League Express editor MARTYN SADLER reviews a welcome addition to the Rugby League bookshelves

TONY COLLINS has done Rugby League a great service by writing about a man who was an outstanding individual by any measure, with many great ach