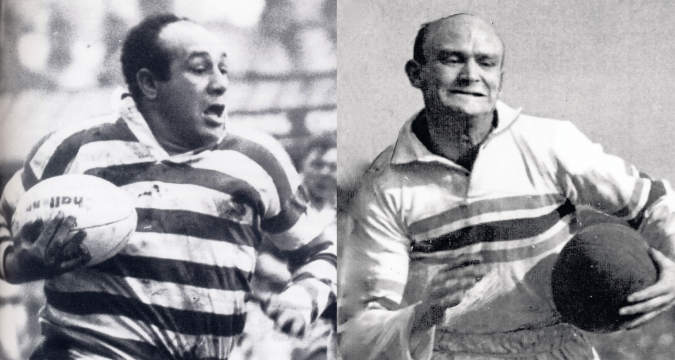

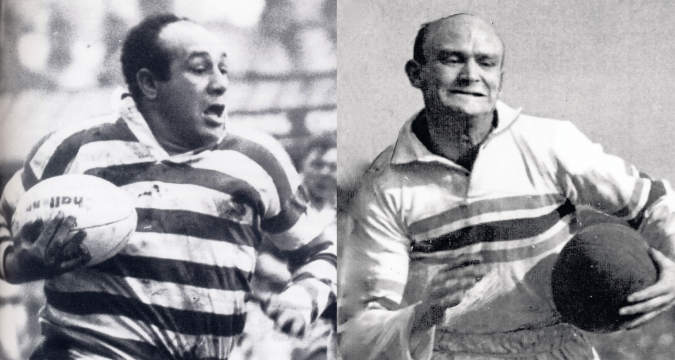

Who is the greatest rugby league try scorer of them all? Only two players have topped the 500 mark, and despite sharing initials, they couldn't be more different.

THE WORLD of rugby league got excited back in October 2022 when Ryan Hall joined the list of players to have scored 300 career tries. It’s a remarkable achievement and it would be chur

Who is the greatest rugby league try scorer of them all? Only two players have topped the 500 mark, and despite sharing initials, they couldn't be more different.

THE WORLD of rugby league got excited back in October 2022 when Ryan Hall joined the list of players to have scored 300 career tries. It’s a remarkable achievement and it would be chur RLW 500: The two legends to reach 500 rugby league tries – and what made them so different

Who is the greatest rugby league try scorer of them all? Only two players have topped the 500 mark, and despite sharing initials, they couldn't be more different.

THE WORLD of rugby league got excited back in October 2022 when Ryan Hall joined the list of players to have scored 300 career tries. It’s a remarkable achievement and it would be chur

Who is the greatest rugby league try scorer of them all? Only two players have topped the 500 mark, and despite sharing initials, they couldn't be more different.

THE WORLD of rugby league got excited back in October 2022 when Ryan Hall joined the list of players to have scored 300 career tries. It’s a remarkable achievement and it would be chur